Do you feel panicked by weather stories?

As atmospheric rivers and "weather bombs" continue to make waves in headlines across the country, Environment Canada asks readers to give pause. While rooted in fact, these descriptors often take on a life of their own, causing alarm among people who may have suffered through a severe weather event.

But some weather phenomena are strong indicators of future weather patterns.

La Niña is of these weather events, and it has powerful ramifications across the globe. In British Columbia, its presence typically means a cold winter with above-average precipitation — which is generally great news for skiers and snowboarders hoping for a season full of champagne powder.

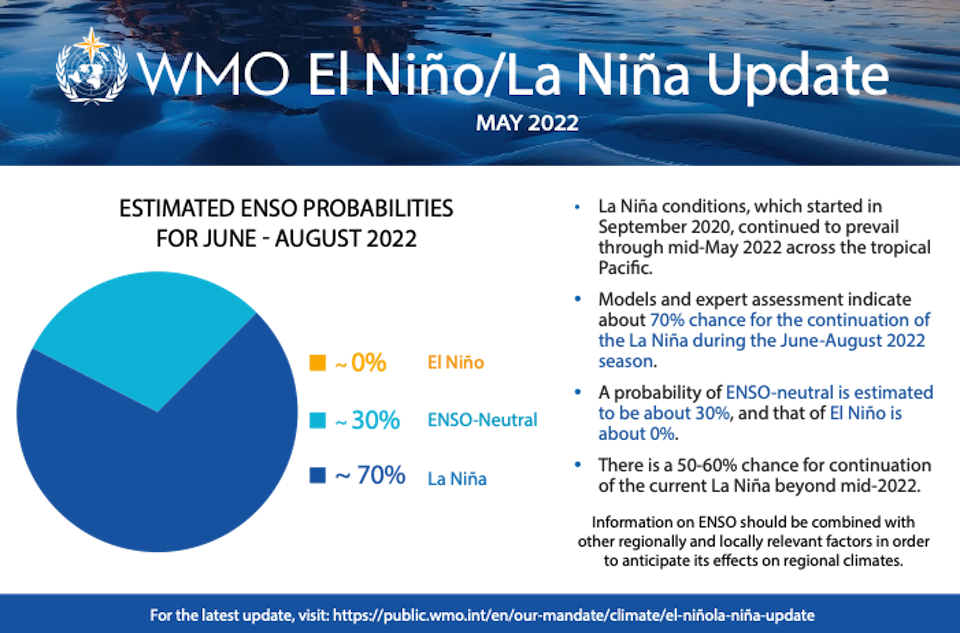

Now, a recent report from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) includes a 70 per cent likelihood of a "protracted" La Niña event that lasts through August 2022.

There have been La Niña events over the past two winters in the northern hemisphere. If this one persists through the winter and into 2023, it would be only the third time since 1950 that this "triple-dip" scenario has occurred, according to the WMO.

Metro Vancouver weather: "Triple Dip" La Niña forecast

La Niña, "the girl" in Spanish, names the "appearance of cooler than normal waters" in the equatorial Pacific Ocean, according to the Canadian government; it is the opposite of an El Niño weather event.

While the weather phenomenon has occurred for centuries, the WHO points out that "all naturally occurring climate events now take place in the context of human-induced climate change, which is increasing global temperatures, exacerbating extreme weather and climate, and impacting seasonal rainfall and temperature patterns."

Environment Canada meteorologist Bobby Sekhon told Vancouver Is Awesome that the presence of the cooler waters so early in the year isn't a strong enough indicator of what will happen in Metro Vancouver next winter.

While he acknowledged the phenomenon can have a profound impact on local weather, he said the region doesn't start to see the cold weather event's impact until late December.

"Usually around Christmas time...that's when you start to see the influence of it," he said. "Sometimes it's not until later. I think it was 2021 where we didn't see really effects of it until February."

Sekhon couldn't say whether the cumulative effect of three La Niña years in a row would have a more dramatic impact locally, but he emphasized that the event doesn't always produce extreme weather.

"Also just keeping in mind...we're looking at a pretty moderate probability," he noted. "The percentage isn't like super high...70 per cent for the summer. By the winter that percentage is a lot lower, according to the report."

But cooler-than-average waters off B.C.'s south coast are currently impacting local weather, notes Sekhon. These waters are part of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), which has a direct impact on local weather and produces cooler-than-average temperatures in its "negative phase."

When will the waters warm up?

A ridge of high pressure can create warm, stagnant air that warms sea surface temperatures, notes Sekhon. And as July approaches, one of those is likely on its way.

With a file from Megan Lalonde.