Exposure to air pollution in Canada is leading to nearly 8,000 deaths per year, says a new study.

The research, published today in a Health Effects Institute (HEI) report, looked at mortality in 7.1 million Canadians over the past 25 years.

Long-term exposure to particulate matter (PM2.5) was found to be the most harmful when combined with other pollutants like ozone. As of 2016, it led to 7,848 deaths per year, though that's likely a lower estimate compared to what Canada is experiencing now.

But even low concentrations of PM2.5 — a pollutant vaulted into the air from wildfires, wood-burning stoves and fossil fuel emissions from cars and trucks — were found to contribute to increasing the risk of death in people already suffering from cardiovascular and heart disease, diabetes, pneumonia or a respiratory disease like COPD.

“There's really no safe level of air pollution,” said the study's lead author Michael Brauer, a professor at the University of British Columbia's school of population and public health.

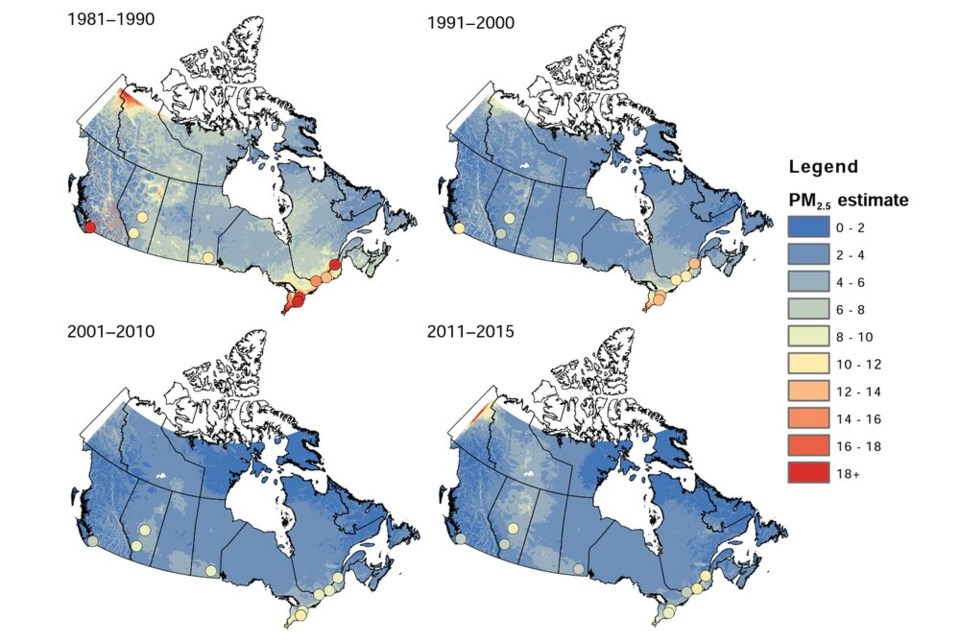

Brauer and his colleagues combined data from satellites, local air sampling and atmospheric modelling to measure PM2.5 concentrations across Canada from 1981 to 2016.

After analyzing the data, the researchers found cities had particulate matter concentrations between nearly three and eight times higher than rural areas. Up until 1990, the highest PM2.5 concentrations were found in big cities, including Vancouver, Toronto, Hamilton and Quebec City.

And while those pollutant levels declined in the following years, even low levels were found to increase the risk of premature death.

'We picked the low-hanging fruit'

Brauer's data temper the results of a study released last year, in which Health Canada estimated all forms of air pollution contribute to the early death of 15,300 Canadians every year.

In that study, B.C.’s Interior suffers some of the greatest fallout from air pollution in the country.

Between 2013 and 2018, the 10 census divisions in the country with the greatest exposure to PM2.5 were all in B.C.’s Interior, according to a 2021 Health Canada analysis of the impacts of air pollution on human health.

Of those, half the census divisions — including Central Kootenay, where Nelson is located — were among the top 10 slices of the country with the highest per capita rates of premature death.

Brauer said climate change, from increased temperatures in cities to devastating wildfires, threatens a lot of the progress that has been made in recent decades.

“We picked the low-hanging fruit,” he said. “With a warmer climate, things are not likely to get better without more aggressive action... And the faster that we decarbonize. the faster we're going to eliminate these health impacts.”

The growing impact of bad wildfire seasons has led some medical professionals to rethink the way they diagnose health crises. After a record heat wave and brutal fire season, one B.C. doctor even diagnosed a patient as suffering from “climate change.”

“A lot of people in the Kootenays sort of thought that this would be a good place to hide out while the rest of the world falls apart. But it's, of course, hitting us here, just like it's hitting many places, and we're really seeing the impacts,” said Dr. Kyle Merritt, head of Kootenay Lake Hospital in Nelson.

Air pollution's global death toll likely much higher

Across the world ever year, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates outdoor air pollution leads to about 4.2 million deaths. Brauer's research would up that estimate by another 1.5 million.

Yet few jurisdictions have air quality standards that reflect the risk Brauer found in his study. Canada’s 2012 Ambient Air Quality Standards set a path to reduce air pollutants in a phased approach through 2025. The current standards recommend PM2.5 concentrations below 8.8 micrograms per square metre.

In the U.S., national standards sit at 12 micrograms per square metre.

The WHO's recently updated standards, meanwhile, drop that threshold to 5 micrograms per square metre.

But none of those pollution limits meets the limit of 2.5 micrograms per square metre, beyond which Brauer says increases mortality risk.

That should be a signal to regulatory bodies both in Canada and around the world that air quality standards need to be strengthened, said Brauer.

“Globally, it means we need to get on with it,” he said. “This is going to be there — even relatively clean countries, Western Europe, North America... there's still significant impact.”

The UBC-led study is the latest in a series of HEI-backed studies looking at how even low levels of outdoor air pollution affect human health.

The first, a 2021 study looking at the effects of particulate matter, black carbon, nitrogen dioxide and ozone across 11 European countries, found “significant” links between those exposed to low levels of pollution and early mortality in people with cardiovascular and respiratory disease, and lung cancer.

The second report, released earlier this year and focusing on the United States, tracked low levels of air pollution exposure in 68.5 million older Americans. Once again, the story was repeated: even low levels of exposure to particulate matter increase the risk of death.