WASHINGTON (AP) — Jurors have gone home for the long Thanksgiving weekend after deliberating most of Tuesday in the Jan. 6 Capitol riot case accusing Oath Keepers founder Stewart Rhodes and four of his extremist group associates of a violent plot to stop the transfer of presidential power from Republican Donald Trump to Democrat Joe Biden.

Federal prosecutors are asking the jury to convict the defendants of seditious conspiracy — a rarely used charge that carries up to 20 years in prison and can be difficult to prove.

The jury began deliberating Tuesday after final arguments wound up late Monday.

Prosecutors spent weeks showing jurors messages, recordings and surveillance video they say show Rhodes, of Granbury, Texas, and his band of antigovernment extremists were prepared to take up arms to overturn Biden’s election victory over Trump.

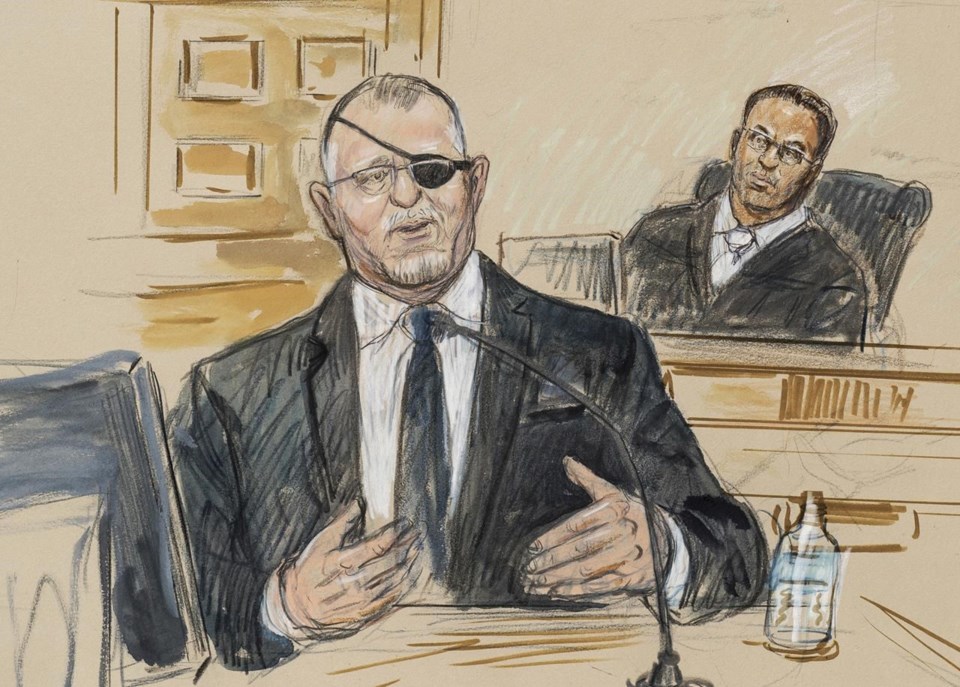

Rhodes and two of his co-defendants — Thomas Caldwell, of Berryville, Virginia, and Jessica Watkins, of Woodstock, Ohio — took the witness stand and sought to downplay their actions and portray the riot as a spontaneous outpouring of election-fueled rage instead of the result of a preconceived plot.

The others on trial are Kelly Meggs, of Dunnellon, Florida, and Kenneth Harrelson of Titusville, Florida. Besides seditious conspiracy, all five defendants face other felony charges. If found guilty of seditious conspiracy, they would be the first defendants convicted of the Civil War-era offense at trial in nearly 30 years. The last successful case was the prosecution of Islamic militants who plotted to bomb New York City landmarks.

The defendants also face several other charges, including conspiracy to obstruct an official proceeding— Congress’ certification of Biden’s 2020 election win.

Rhodes told jurors there was no plan for the Oath Keepers to attack the Capitol and said his followers who went inside acted “stupid.”

The jury will weigh the charges that the Oath Keepers were not whipped into an impulsive frenzy by Trump on Jan. 6, 2021, but traveled to Washington intent on stopping the transfer of presidential power at all costs.

The riot was the opportunity they had been preparing for, prosecutors say. Rhodes’ followers sprang into action, marching to the Capitol, joining the crowd pushing into the building and attempting to overturn the election that was sending Biden to the White House in place of Trump, authorities allege.

Not true, the Oath Keepers argue. They say there was never any plot, that prosecutors have twisted their admittedly bombastic words and given jurors a misleading timeline of events and messages.

Hundreds of people have been convicted in the deadly attack, which left dozens of officers injured, sent lawmakers running for their lives and shook the foundations of American democracy. Now jurors in the case against Rhodes and his associates, for the first time, will need to decide whether the actions of any Jan. 6 defendants amount to seditious conspiracy — a charge that carries both significant prison time and political weight.

Failure to secure a seditious conspiracy conviction could spell trouble for another high-profile trial beginning next month, of former Proud Boys national chairman Enrique Tarrio and other leaders of that extremist group. The Justice Department’s Jan. 6 probe has also expanded beyond those who attacked the Capitol to focus on others linked to Trump’s efforts to overturn the election.

In the Oath Keepers trial, prosecutors built their case using dozens of encrypted messages sent in the weeks leading up to Jan. 6. They show Rhodes rallying his followers to fight to defend Trump and warning they might need to “rise up in insurrection.”

“We aren’t getting through this without a civil war. Prepare your mind body and spirit,” he wrote shortly after the 2020 election.

A government witness — an Oath Keeper cooperating with prosecutors in hopes of a lighter sentence — testified that there was an “implicit” agreement to stop Congress’ certification but the decision to enter the building was “spontaneous.”

“We talked about doing something about the fraud in the election before we went there on the 6th,” Graydon Young told jurors. “And then when the crowd got over the barricade and they went into the building, an opportunity presented itself to do something. We didn’t tell each other that.”

Prosecutors say the defense is only trying to muddy the waters in a clear-cut case. The Oath Keepers aren’t accused of entering into an agreement ahead of Jan. 6 to storm the Capitol.

Defense attorneys for Caldwell, Watkins and Harrelson worked on Monday to cast doubt on the timeline presented by prosecutors, saying that communications were hampered by overwhelmed cell towers and that other rioters forced Congress to recess before they arrived.

Prosecutor Jeffrey Nestler, though, said any lag was brief and the Oath Keepers were among the rioters who interrupted congressional proceedings by preventing lawmakers from coming back into session to certify the presidential vote.

Citing the Civil War-era seditious conspiracy statute, prosecutors tried to prove the Oath Keepers conspired to forcibly oppose the authority of the federal government and block the execution of laws governing the transfer of presidential power. Prosecutors must show the defendants agreed to use force — not merely advocated it — to oppose the transfer of presidential power.

After the riot, Rhodes tried to get a message to Trump through an intermediary, imploring the president not to give up his fight to hold onto power. The intermediary — a man who told jurors he had an indirect way to reach the president — recorded his meeting with Rhodes and went to the FBI instead.

___

Richer reported from Boston.

___

Follow the AP's coverage of the Capitol riot at https://www.apnews.com/capitol-siege. And for more on Donald Trump-related investigations, go to https://apnews.com/hub/donald-trump.

Michael Kunzelman, Lindsay Whitehurst And Alanna Durkin Richer, The Associated Press