Under the din of an industrial alarm, dozens of engineers stare at their screens, braced for the unexpected.

“Ready to fire!” shouts the lead operator. “Firing!”

A powerful discharge of electricity sends a muffled clap across the control room. On the other side of a protective wall of shipping containers, a donut-shaped ring of super-heated plasma flickers to life.

A few minutes later, data from inside a new fusion test reactor pours into several computer terminals.

“Every time we do this, we learn a little bit more,” says Mike Donaldson, senior vice-president of technology development at General Fusion.

In a warehouse near Vancouver’s international airport, the B.C. company has grown to become a contender in the race to produce the world’s first fusion power plant.

General Fusion claimed it hit a major milestone last month when it turned on its new LM26 test reactor—a fusion machine designed at half the scale of what could one day power 150,000 homes.

Bottling the power of a star

Largely fuelled by seawater, fusion promises a nearly unlimited clean source of electricity without climate-warming gases, nuclear waste or the threat of a runaway reaction.

Unlike nuclear fission, which releases energy by splitting atoms, fusion is achieved by smashing atomic particles together in the same way energy is made in a star. Inside our sun, an immense gravitational field crushes super-heated hydrogen atoms together, producing helium and massive amounts of heat and energy in the process.

Without the gravity of a star, however, scientists on Earth have spent decades struggling to recreate those same conditions.

Some—like the massive multi-national ITER tokamak fusion reactor set to be completed in France in 2033—have turned to powerful magnets to both crush and insulate plasma as it heats up to 200 million degrees Celsius.

Others have relied on high-energy lasers to quickly zap hydrogen plasma to extreme temperatures. In December 2022, the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California fired the world’s most energetic laser at a centimetre-long gold cylinder, instantly vaporizing it.

Inside, a diamond fuel capsule filled with deuterium and tritium imploded, forcing the hydrogen isotopes into each other with such force they combined to create helium.

For the first time, scientists reached “ignition”—and for a brief moment, the fusion reaction produced twice the energy needed to fire the laser.

At the time, then U.S. Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm described the breakthrough—also known as “scientific break-even”—as “one of the most impressive scientific feats of the 21st century.″

Last month, the team successfully repeated the experiment a sixth time.

Richard Town, who leads the U.S. fusion program, said their successful ignitions are isolated to experiments, and shouldn’t be confused with a scalable fusion reactor that could one day be deployed in a power plant.

“It wasn’t designed to be a commercial power plant,” said Town. “It was designed to understand the physics of what’s going on in a fusion reaction.”

Early fusion prototypes designed with power plant in mind

From the beginning, Michel Laberge had other plans. Originally from Quebec, the physicist completed a PhD at the University of British Columbia investigating laser-powered fusion. But he soon became disenchanted with its potential.

To reach and maintain fusion temperatures, most scientists had either turned to quickly heating up plasma with lasers or insulating reactors with a blanket of super-magnets. Neither method, according to Laberge, could easily be scaled up into a commercial power plant.

About 25 years ago, he rented out a garage at an old service station on Bowen Island and set to work building a mechanical alternative.

Early test reactors looked like oversized stainless steel bowling balls wrapped in explosives. Laberge lined an inner fuel chamber with polycarbonate to absorb the shock wave. When the scientist detonated the devices in a field, the metal casing quickly imploded, crushing the fuel inside.

The first tests were discouraging. Much of the plasma escaped. But after some adjustments (Laberge swapped out explosives for a sphere of high-powered pistons), the magnetic field started to get bigger and the plasma denser.

Later experiments released even more energy, evidence that collapsing a wall of metal around plasma could trigger a fusion reaction.

The Canadian government began investing in the company, and since 2019, has poured $69 million into General Fusion. The federal dollars have helped attract a total of $440 million in private capital, enough to expand its workforce to 120 employees and advance a series of prototypes, including the world’s most powerful fusion plasma injector.

New test reactor aims to prove company's tech works

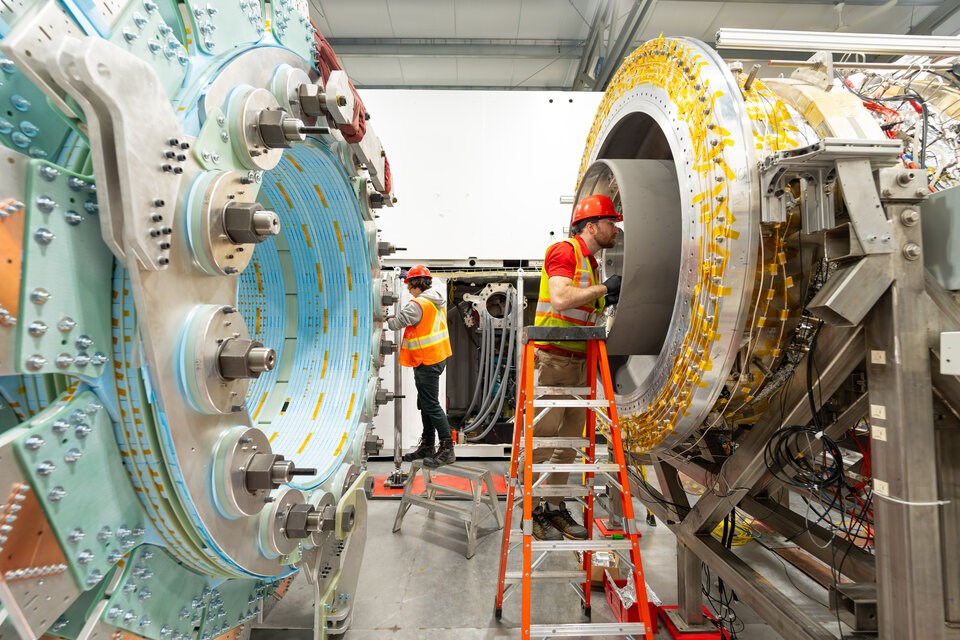

General Fusion’s latest two-metre-wide test reactor was completed three weeks ago in a Richmond warehouse.

From a distance, LM26 might easily be confused with the business end of a rocket or satellite getting prepped for launch. Thick black electric cables snake out across the floor.

Stacks of converted shipping containers surround the machine, each containing batteries and capacitors designed deliver up to a gigawatt of power—nearly enough to send Marty McFly and a time-travelling DeLorean into the future.

Back in the control room, the red outline of a donut-shaped ring of plasma fills one engineer’s screen.

“If we can get that donut to hold in its heat well enough, we can compress it using pistons rather than using, like, the world's biggest laser,” said Donaldson.

Donaldson says those tests will begin in the next few weeks. Once a week, engineers will crush the fusion fuel inside a metal chamber. Temperatures are expected to ramp up from the current four million degrees Celsius to 100 million degrees by 2026.

By 2027, the new half-size reactor will serve as a test machine to prove the company’s design can release more energy than it consumes.

The next step will be to swap out the solid metal cans inside the reactor with a liquid metal chamber designed to solve three engineering problems.

Unlike the current test reactor, a bubble of liquid lithium can be crushed multiple times without being replaced. That’s a critical feature if a power plant is to continuously produce power, says Laberge.

The liquid metal chamber is also designed to shield the machine from high-energy particles produced by fusion. The result, claims the company, is a power plant that can operate for decades.

Then there's the question of fuel. Deuterium isotopes can be extracted from seawater. But tritium, a second isotope used in the fusion machine, is not found in nature, making it a scarce and therefore expensive fuel.

General Fusion liquid lithium core is designed to produce an indefinite supply of tritium.

“We can actually make more tritium than we burn,” Laberge said.

If LM26’s tests are successful, General Fusion claims it will need another seven years to scale up the machine into a working power plant.

Where in the world that fusion plant would be built remains an open question, although General Fusion has a standing offer from the United Kingdom to build an intermediate machine in partnership with the country’s atomic energy agency.

“We have a way of doing fusion that would make a great power plant,” said Donaldson. “What we have to show next is that the fusion actually works.”

The race to fusion accelerates

General Fusion is among a handful of start-ups promising to move from experiments into real-world power plants. It has some stiff competition.

Commonwealth Fusion Systems has a nearly identical timeline to General Fusion: It aims to prove its magnetic fusion technology works by 2027, with plans to build a working power plant in Virginia by 2033. Spun out of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the company has raised US$2 billion in capital—more than any other fusion start-up.

And across the border in Seattle, Helion Energy says that by 2028, it will start generating electricity for Microsoft by firing two rings of plasma at each other.

It’s not clear if any of the aggressive timelines to commercialize fusion are realistic. Over the past several decades, fusion’s proponents have claimed the technology was poised to revolutionize global energy, only to face further delays.

From his office in Livermore, Calif., Town said he believes fusion will one day become commercially viable, but that scientists remain in “discovery mode” with a lot more work still to be done.

While the U.S. lab is largely focused on research to advance national security, scientists working there are keenly aware that its success in 2022 could eventually help reshape the future of sustainable energy.

Consider this moment as the Wright Brothers’ first flight, said Town. They proved aviation was possible, but it wasn’t until years later that people regularly boarded aircraft to cross oceans and continents.

If fusion can be turned into a commercial reality, Town said it will democratize energy in the same way flight reshaped the way people travel. That, he added, would be good for everyone.

“You get to this point where we don’t have to worry so much about climate change,” he said. “It’s not really if, it’s when.”

———

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story stated General Fusion plans to ignite fusion in its new LM26 machine. In fact, the company plans to show its technology can produce the equivalent of scientific break-even, using only deuterium as fuel, by 2027.

Further, the $440 million in investment the company has received includes government funding.

Stefan Labbé