The carnivorous purple sea star, Pisaster ochraceous, is an echinoderm (echinos = hedgehog; derma = skin), related to sea urchins, sand dollars, and sea cucumbers, found in the intertidal zone of the Pacific Northwest.

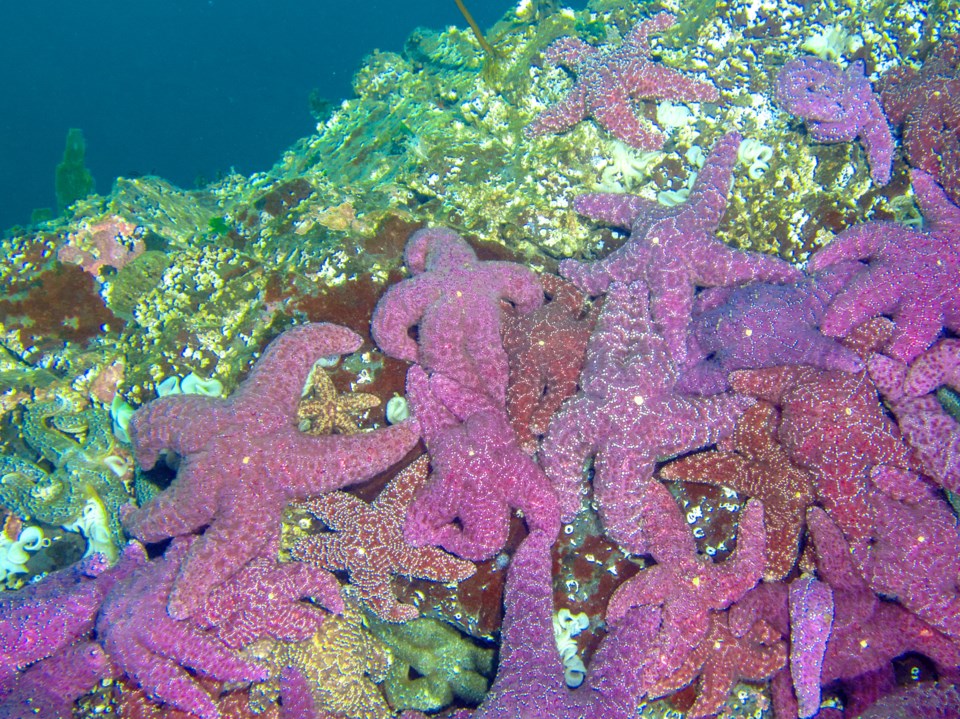

This colourful species, ranging from orange to deep purple, grows up to 25 cm from arm to arm, may live up to 20 years, and is strong enough to pull their preferred prey of mussels off the rocks and drag them deeper into the ocean to eat them. If they cannot pull the mussel off, the sea star will cough up its stomach, and sneak into the clam or mussel through openings as small as one-tenth of a millimeter. It will proceed to digest its prey from the inside-out. It will then contract its muscles and pull the stomach back in.

Robert Paine, with the University of Washington, noticed that when P. ochraceous was abundant the diversity of the intertidal community was higher than in its absence. From this observation, he proposed the concept of a keystone species. An organism that falls into this category plays a critical role in maintaining the ecological structure of its community.

When Paine and his collaborators systematically removed a group of sea stars (a tird, such a group is called) from a habitat, more than 20 species of other invertebrates disappeared. The Mytilus californianus, or California mussel, took over (and this mussel, as it happens is the sea star’s favourite prey). Thus, the presence of the purple sea star can be used as an indicator of the “health” of the intertidal zone, if one considers a healthy intertidal zone to have a higher diversity of species.

According to Bowen Island diver and marine enthusiast Adam Taylor, Pisaster ochraceous have not suffered as much as other kinds of sea stars from the recently reported die-off of sea stars in the Pacific Northwest. This has been caused by Sea Star Wasting Disease.

“My personal observations from 70-odd dives over the past year are that sunflower stars had a 99% die-off and other stars saw a 25-75% die-off,” says Taylor. “There is no 'smoking gun' as to the cause but most experts feel that the recent overpopulation of sunflower stars left them vulnerable to disease. They were literally stacked on top of each other and were eating almost everything in the 10-45 foot depth range. They were beautiful to see but it was obvious that they were overpopulated.”

Taylor says that the purple sea star populations face other threats.

“Their numbers have been in decline for the past 25 years or so. There used to be huge rafts of them along Bowen's rocky shorelines, sometimes 100 metres long. A parasite has been eating the male gonads, lowering their numbers and limiting their population. This is essentially a parasitic castration.”

Denis Lynn is a professor emeritus in integrative biology, University of Guelph, and an adjunct professor in Zoology, University of British Columbia.