Decades after Ballard Power Systems (TSX, NYSE:BLDP) helped establish Metro Vancouver as a clean-tech hub, the presence of nuclear power player General Fusion appears to be pulling talent and investment into B.C.’s clean-energy sector.

Type One Energy, an American fusion power startup, recently raised US$29 million ($39 million) in seed funding and has opened a research office in Vancouver. General Fusion’s former CEO, Christofer Mowry, is now CEO for Type One Energy.

Type One is the second nuclear energy company to recently set up offices in Metro Vancouver. Dual Fluid Energy, a German-Canadian nuclear energy startup, also recently moved into Vancouver, partly due to its relationship with the TRIUMF National Laboratory at the University of British Columbia.

While Dual Fluid is in the fission space, and General Fusion in the fusion space, both are nuclear energy companies that are leveraging TRIUMF’s expertise in particle physics for materials testing and diagnostics.

In explaining its decision to open an office in Vancouver, Type One Energy noted that Metro Vancouver is home to one-quarter of Canada’s clean-tech companies, which collectively raised $800 million across 55 deals during the first nine months of 2023.

Canada’s immigration and foreign worker permit policies also make it easier to import scientists and engineers from other countries – a competitive advantage it has over the U.S.

“It allows us to attract talent from all around the world, but the primary reason really is the ecosystem that’s already existing in Vancouver in the clean-tech space, and in particular fusion, and that talent that’s available in that surrounding area,” Type One Energy CFO David Vickerman told BIV.

“Obviously, the Pacific Northwest, including Seattle, there’s a cluster of both technical engineers and fusion scientists. So our primary reason is to take advantage of that talent pool.”

According to the Fusion Industry Association, as of last year, there were 33 private fusion energy companies in the world. General Fusion is among a handful – along with Commonwealth Fusion, TAE Technologies and Helion Energy – that have raised the most in venture capital and are furthest along in the race to build a workable fusion power reactor.

“There is already a nuclear fusion cluster here, with companies like General Fusion and their wide participation with Canadian institutions like TRIUMF, CNL [Canadian Nuclear Laboratories], many universities, Bruce Power and others,” said Wal van Lierop, founder and CEO of the clean-tech venture capital firm Chrysalix Venture Capital, one of General Fusion’s early investors.

“The success of General Fusion and Commonwealth and others attracts other young companies trying to ride on the coattails of these leading companies.”

While there are different designs being tested, the basic principle in fusion energy is the same: Force lighter atoms (hydrogen isotopes of deuterium and tritium) to fuse into heavier ones (helium) through intense heat and pressure to release energy.

This requires containing super-hot plasmas and exerting tremendous force to start the fusion reaction. One approach is magnetic confinement using powerful magnets.

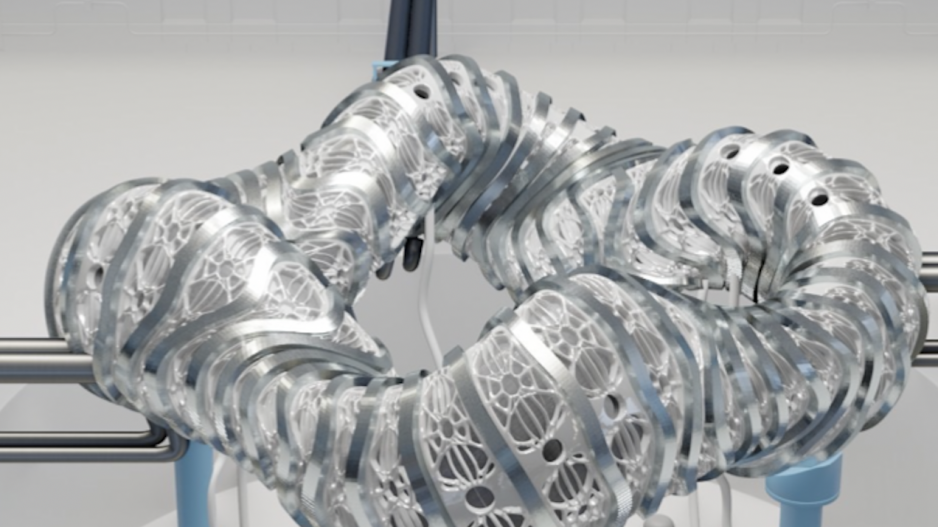

A common design for magnetic confinement is a tokomak machine, which contains super-hot plasma in a donut shape, called a torus. Type One’s stellarator design is more pretzel than donut, in that it uses “twisted magnetic fields.”

Two prototype stellarators have been built – the HSX, built by the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and the Wendelstein 7-X (W7X) built by the Max Planck Institute for Plasma Physics in Germany.

Three of the scientists involved in the HSX project are co-founders of Type One Energy, and one of the scientists involved in the W7X prototype is on Type One’s technical leadership team.

“We have some of the leading scientists, not only in fusion, but in the stellarator space on our team to help us commercialize this technology,” Vickerman said.

Stellarators have several advantages over tokamaks, according to the U.S. Department of Energy: “Stellarators require less injected power to sustain the plasma, have greater design flexibility, and allow for simplification of some aspects of plasma control. However, these benefits come at the cost of increased complexity, especially for the magnetic field coils.”

Advancements in computing power and superconducting magnets have helped scientists and engineers overcome some of the technical challenges that previously plagued the stellarator.

“W7X and HSX were built using low-temperature, super-conducting magnets, where now the advancement in high-temperature super-conducting magnets enables us to use that technology to increase the field strength without increasing the size of the machine,” Vickerman said. “So both reduction in cost but increase in performance.”

Type One currently employs 10 people in its new Vancouver office on West Pender Street.

“We would look to probably double that this year,” Vickerman said.