Labour costs are replacing oil products as a mine’s most expensive item as inflation impacts operating expenses more than capital costs, new reports show.

Wages for some copper and gold mine employees in the southwest United States increased by around 10% in the last year and a half, helping raise hourly pay by 4% at unionized and non-union surface and underground metal and industrial mineral mines across the U.S., according to Costmine Intelligence, a unit of The Northern Miner Group.

The trend is part of 30% higher labour costs since the 2015 commodity bear market, Costmine vice-president Mike Sinden said in a recent interview. Barring another oil price shock, U.S. workforce costs are expected to be the fastest increasing element in a mine’s expenses, Sinden said. For open pit mines, he says labour could exceed half of their costs.

“As non-unionized labour gains bargaining power and union contracts roll off, we expect to see double-digit labour costs,” Sinden said. “That could really add fuel to the fire if energy prices stay strong.”

Labour costs are rising in Canada and the U.S. at a similar pace when accounting for foreign exchange. Until 2021, wage cost increases largely matched inflation at around 2% to 4%, but last year saw some pay increases of 5% to 12%, Costmine data show. Salaried staff saw similar increases.

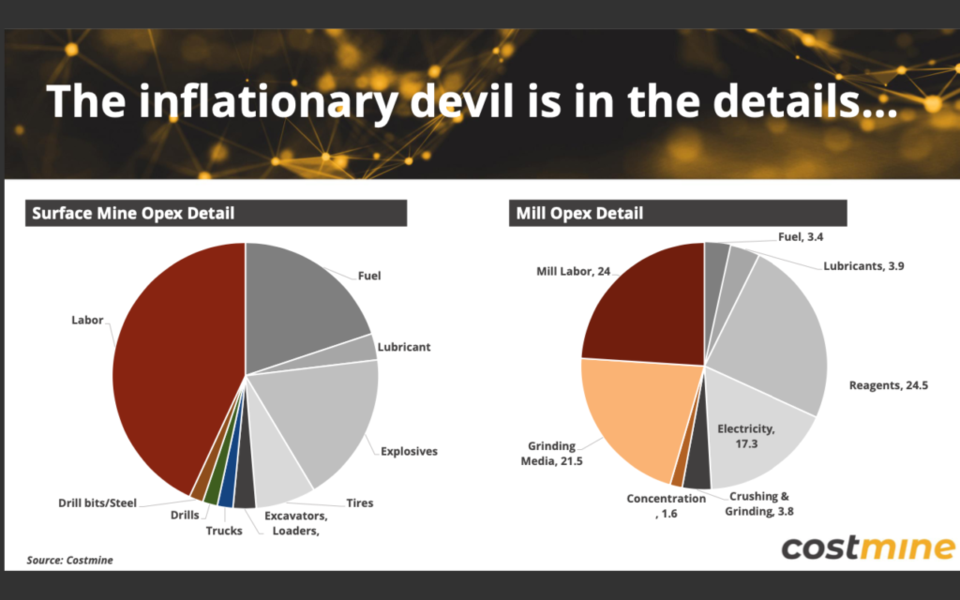

The workforce accounts for some 43% of operating costs at a surface mine while oil-based products — such as fuel, explosives and tires — account for just less than half, Costmine data show. Labour costs at 24% is less of a component to run a mill, where 21.5% of operating costs is grinding media. But oil-based products make up about half of the mill’s operating expenses.

The price of a common big-ticket item, a 100-ton hauling truck, has increased little from US$1.6 million eight years ago, but the cost of running it has rocketed the most on a Costmine index of operating expenses that also included a locomotive and a conveyor belt.

A truck that was US$108 an hour to run in 2015, cost US$175 an hour last year. There have also been a number of reports of underground jumbo drill operators earning US$100 an hour, two to three times what Costmine has tallied in the past, Sinden said. As forecasts call for constructing hundreds of mines for the metals to tackle climate change, there’s bound to be a crunch.

“The theme is going to be cost inflation,” Sinden said. “Everyone’s going to rush to develop a mine, going to want labour, want a jumbo drill and 100-ton trucks. And the next 10 years are going to be really spicy when it comes to inflation.”

One somewhat hidden aspect of the pay raises is the role bonuses have increasingly played over recent decades, Sinden said. Some 70% of U.S. mines offer bonuses, many tied to production, attendance and commodity prices. They will further drive wage inflation if shortages spur metal price hikes.

The bonus figure for Canada is about 41% of mines, but data are incomplete, Costmine says. In the U.S., bonus plans are found at about 90% of coal mines, which can siphon 5% to 15% of a mine’s profit. Coal prices shot up after the war in Ukraine cut off Russian gas supplies to Europe, and metallurgical coal for steel production similarly rocketed. Only about 20% of coal mines offered bonuses in the 1980s, Sinden said.

Globally, a semblance of parity in surface mine operating costs is emerging among jurisdictions, Costmine data show. Australia has the smoothest trends compared with the U.S. and Canada because 52% of its costs are attributable to unionized labour. Still, Canada has just under 90% of its mine employees unionized, while it’s about 43% in the U.S., Costmine says.

That means the impact of inflation would be felt slower in Canada because of “sticky” contracts compared with the more flexible U.S. labour market, the analysis unit says.

In capital costs, economies reopening in 2020-21 after the worst of the pandemic drove steel prices higher, then the Russia-Ukraine war increased energy prices, especially metallurgical coal for steel, and supply chain constraints kept prices elevated. Steel prices have since eased but the potential for volatility remains, Sinden said.

Equipment that is more bespoke, such as conveyor belts linking specific operations, tends to show higher inflation than haulage trucks that are common across mines, the data show.

“Ultimately, capex will rely on your view of steel prices and to some degree, copper, zinc and nickel,” Sinden said. “But again, labour could creep into this equation. At current levels, a flattening of capex escalation would be a reasonable assumption, but the labour component of capex could drive the next leg higher in inflation.”