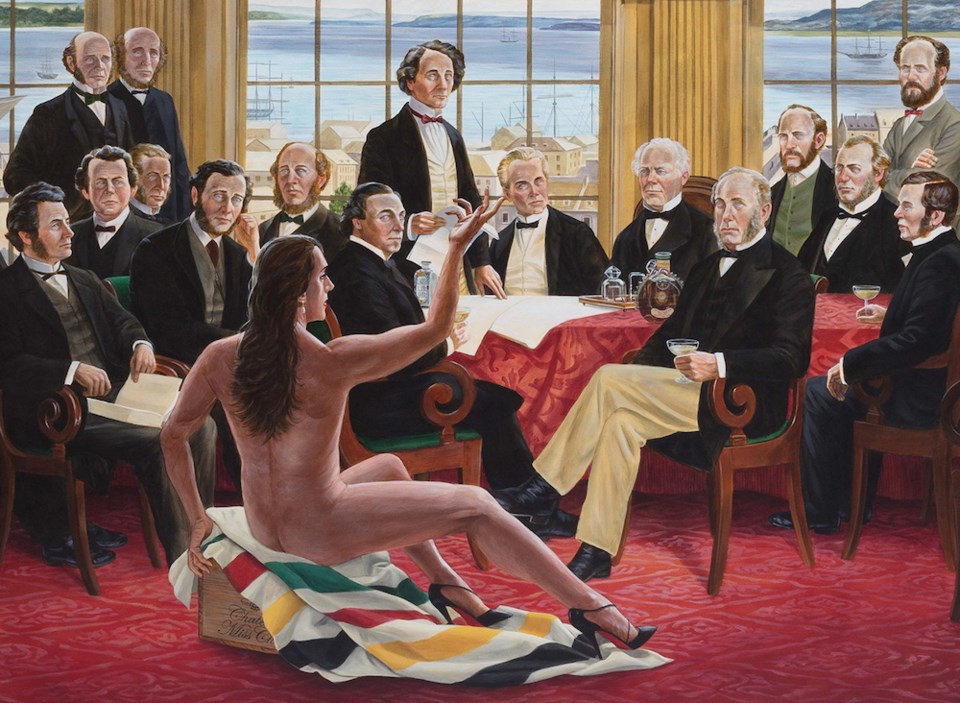

The Fathers of Confederation look so self-assured as they stare out of the portrait celebrating their gathering in Charlottetown in 1864. History, they seem to say, will know their contributions to the creation of Canada.

In the foreground of Robert Harris’s iconic painting — the painting that schoolchildren study in their Canadian history classes — is a cushioned stool with a jacket draped over it.

Well, we are all about to get re-schooled.

Kent Monkman looked at that painting and saw what was missing: the First Nations people upon whose knowledge, mistreatment and ultimate forbearance this country was built.

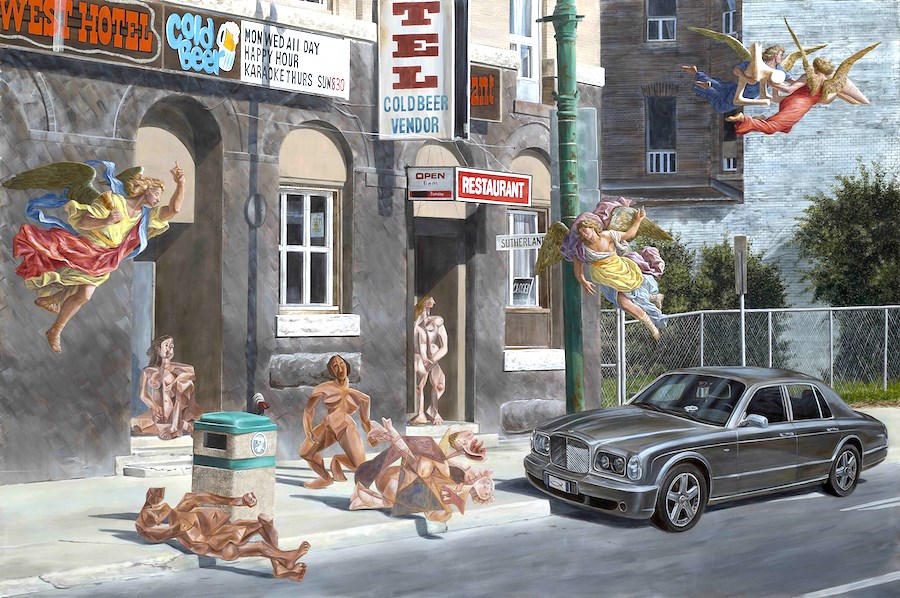

Like Alice falling down a rabbit hole, Monkman uses one of the most intelligent forms of humour — whimsy and wit — to quite literally redress a historical wrong. And he does it through one of the few mediums that can express the inexpressible truths of our humanity. Art.

His “re-storying” of Canadian history is now on display at Vancouver’s Museum of Anthropology as part of an illuminating, challenging, smile-inducing, disturbing and soul-touching exhibit called Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience by Kent Monkman.

Guiding us through the exhibit’s immersive narrative is Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, “a beautiful, time-travelling, gender-bending supernatural being whom Monkman uses as his alter-ego,” explains Dr. Jennifer Kramer, MOA’s curatorial liaison for the exhibit, during an insightful media tour before the exhibit’s official Aug. 6 opening. “Because she’s a time traveller, he can insert her into the history of the interactions in what became Canada.”

So here is Miss Chief in all her wondrously naked female/male glory, legs akimbo, feet adorned in Louboutin heels. She does not allow Harris’s Fathers of Confederation to avert their gaze from her, ahem, “presence” on that cushioned stool (where the jacket is replaced by a Hudson Bay blanket.) These white European men tried to subjugate the First Nations peoples who fought to protect Indigenous land and rights but, in this painting called The Daddies, Miss Chief is the one who dominates. (She becomes a veritable dominatrix in another painting that throws conventional 19th Century battlefield art on its leather-strapped tush.)

And here she is again, only this time as a beautifully coiffed, incredibly life-like mannequin dressed in a baroquely embroidered robe with beaver fur trim while she laconically surveys the exhibit from a swing suspended from the gallery ceiling. Sitting at her feet are the Marquis de Montcalm and Major-General Wolfe, two men once again having their attention diverted away from their history-defining roles on the Plains of Abraham. She swings. They swoon.

This piece is called Scent of the Beaver.

You might gasp at the crudeness — and, once again, sheer wittiness — of the title but Monkman has an ability to both acknowledge sexual shame while taking away shame’s power. (And here’s a double entendre to make Monkman’s humour more sublime: A beaver’s anal gland secretes castoreum, which is a cherished ingredient in perfumes and food flavourings. Or maybe that’s your first reaction to the title and the high school vernacular for a woman’s vagina didn’t cross your mind….)

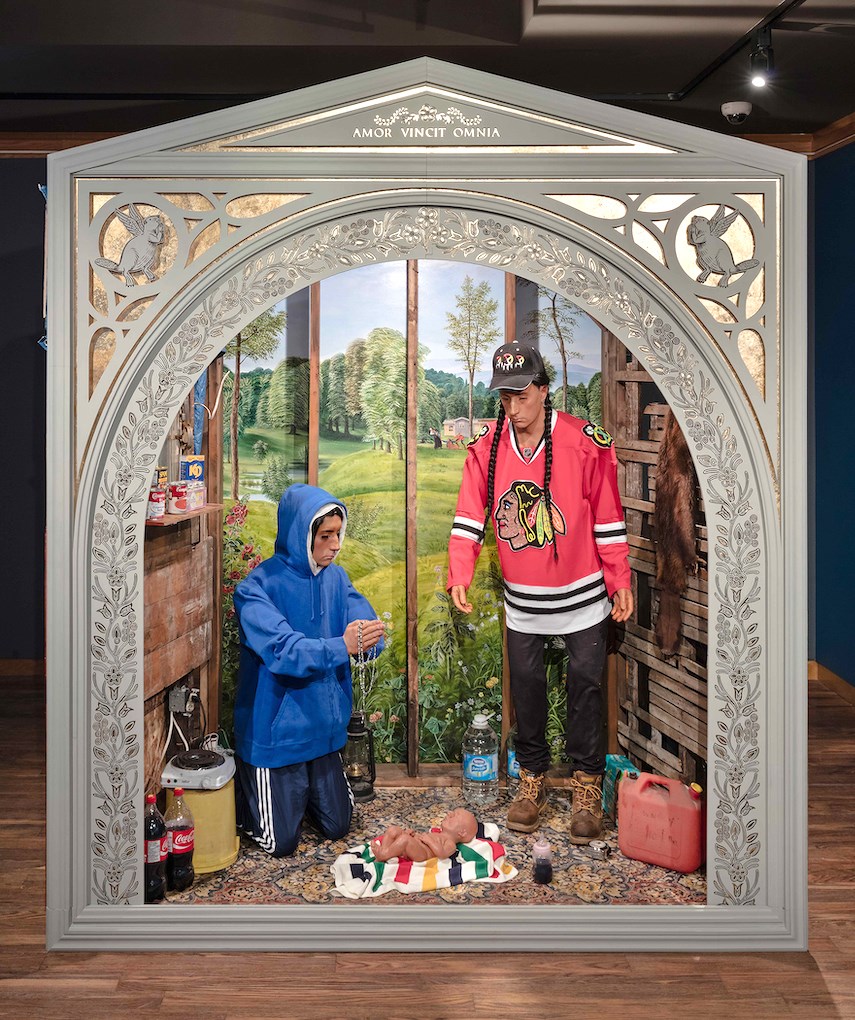

Monkman doesn’t make mischief with our understanding of history in the chapter called The Forcible Transfer of Children. The exhibit room is painted black. On two facing sides are cradleboards, some in chalk outlines, some in plain wood. They look like baby-sized tombstones. (To remind you how intricately beautiful and lovingly made the original baby-carriers were, Monkman also has a few on display.)

The painting on the wall directly facing you is an emotional suckerpunch: The Scream.

You want to look away from the heartache but you can’t as priests, nuns and red-tunicked RCMP officers snatch children away from their mothers. The mothers’ and children’s anguish is not distorted, as it is in the Edvard Munch painting. It’s real and raw. And yet they, like the house in the background, are not painted as historical figures. We are not allowed to reassure ourselves that “This racism happened only in the past. It’s different now.”

In the nine-chapter “memoir” the serves as the inspiration for the nine-part exhibit, Miss Chief writes “This is the one I cannot talk about. The pain is too deep. We were never the same.”

“Monkman shows that there are limits to Miss Chief’s power,” says Dr. Kramer. For all of the religious allegories in many of his works, “he can’t make Miss Chief as the saviour because she wasn’t.”

History happened.

However, Monkman, who is Cree and grew up in Northern Manitoba, goes a long way towards reclaiming it.

Shame and Prejudice is many, many things but there’s one thing it isn’t — dogmatic. Monkman’s not waving a tsk-tsking finger of judgement, but he does expose the wrongs that history will be judged by. He uses humour to trick you into feeling comfortable about his in-your-face way of confronting hard truths, but his supreme skills as a multi-dimensional artist open your heart and mind to where he wants to lead you. Monkman’s references to — and mastery of — classical art reflect his admiration of it even as he appears to mock it. In doing so, he turns the table on cultural appropriation.

This is the first MOA exhibit since the pandemic began. It would be such a loss of opportunity if people don’t feel reassured enough by MOA’s safety restrictions to venture out to the UBC Endowment Lands. After months of engaging in life primarily through our TV and computer screens, there’s something so deeply satisfying about being able to walk through the exhibit, to feel the power of art, to be reminded anew of an artist’s ability to reshape and question our understanding of our world. No online article could ever do Monkman’s work justice. No image on a screen can convey what it’s like to be drawn into his imagination. Book your tour time and go.

Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience is at the MOA until January 3, 2021. As a result of COVID-19, only 50 people will be allowed into the museum at any one time. Tickets will not be sold on site. To limit how many people are in the exhibit space, everyone must book their entry online here but there is no time limit for the length of the visit. There is free admission for Indigenous peoples and MOA members. Masks are strongly encouraged but will not be provided.

Martha Perkins is the North Shore News’ Indigenous and civic affairs reporter. This reporting beat is made possible by the Local Journalism Initiative.