In years past, the most popular swimming beaches on Bowen Island were found on the shores of Mannion Bay. In recent years however, high counts of coliform and fecal coliform in the Bay’s waters have deterred swimmers, and even earned the bay the nickname, “Poo Bay.” This is a point Bruce Russell, the founder of the Friends of Mannion Bay group, brings up frequently in his efforts to drive home the necessity of a major clean-up initiative. According the report outlining possible steps towards a long-term strategy for the Bay, the municipality’s chief bylaw officer, Bonny Brokenshire, notes that in 2012 and 2013, 35 percent of the water samples taken from Mannion Bay contained levels of contamination by fecal coliform bacteria exceeding 200 coliform per 100 millilitres of water, which is the threshold established by the Canadian Recreational Water Guidelines for safe swimming. Last week, council took the step of approving Brokenshire’s recommendation that an environmental assessment be carried out in order to determine the source of the bacteria.

“There is a lot of speculation about where these high counts are coming from,” says Brokenshire. “If we want to mitigate this problem, then we need to understand it better. Maybe the reason the coliform counts are so high is because of the birds. If we know this is the case, we can actually do something about it, but at this stage, we really don’t know.”

Speculation is something that Scott Burch, who lives on a boat that is occasionally moored in Mannion Bay, is also concerned about.

“I keep hearing about this fecal coliform thing and I keep hearing it as a reason to get rid of the boats,” says Burch. “I believe this has become something of a Bowen myth.”

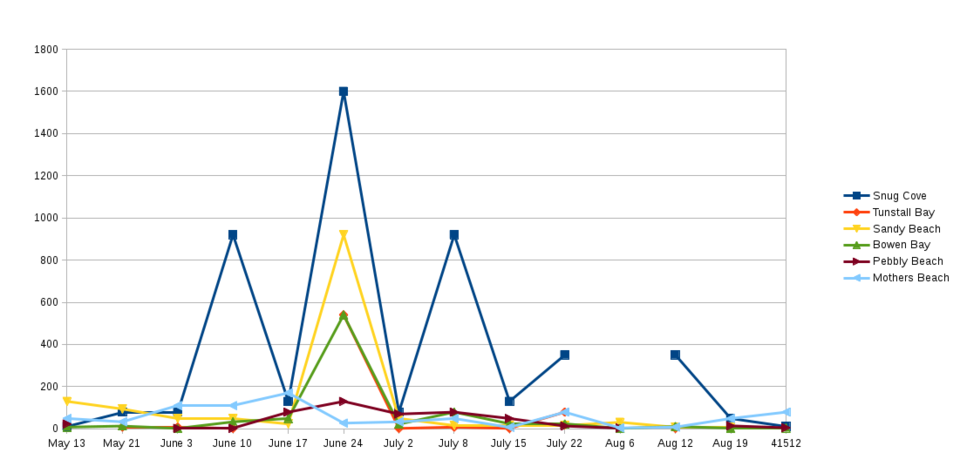

In an effort to understand the situation better, Burch graphed all of the numbers gathered during the weekly tests for coliform that were conducted on Bowen’s main swimming beaches in 2012 and 2013.

“I was actually surprised that they weren’t higher, on Pebbly Beach,” says Burch. “The trend in the samples taken there is well below 200, but there are these huge spikes that are very narrow. When I was a networking engineer, data analysis was a huge part of my job. When I would see huge spikes like that I would see some kind of problem, usually in the method of testing.”

Brokenshire says that there are always improvements that can be made to testing.

“Our public works department conducts all of this testing and our resources are finite,” says Brokenshire. “When we go out and take these samples, there is a protocol: you go knee deep and gather the water just below the surface so that the sediments on the bottom are not disturbed, but the samples are not taken at the same tide level each time, that could make a difference.”

For Bob Robinson, superintendent of public works, the answer to the fecal coliform question is straightforward.

“We see spikes on busy weekends, on long weekends,” he says. “And Pebbly Beach is not the worst, Snug Cove beach is the worst. If you look at 2010 as an example, the coliform levels at Snug Cove beach on July 5th, right after the long weekend, they were up to 880. One week later that level dropped to 320, and a week after that it fell down to 18, which is close to what it was the week before the long weekend.”

Robinson adds that coliform levels at Pebbly Beach are not as dramatic as they are made out to be.

“The highest number at Pebbly Beach last summer was 130,” he says. “If the reason for that was the septic systems on shore, I think we would see that number as consistently high, but its not.”

At a council meeting several weeks ago, Councillor Cro Lucas noted that the environmental consulting firm Pottinger-Gaherty, which has a connection to Bowen Island, could provide some insight on the situation in Mannion Bay.

The Undercurrent spoke with one of the partners of Pottinger-Gaherty, Will Gaherty, about how someone conducting an environmental assessment might approach the issue of high fecal coliform counts in an area.

“Coliforms and fecal coliforms are the bacteria in feces, and testing for them is cheap and relatively easy,” says Gaherty. “These tests are used to indicate whether sewage is present in the water. The problem is, that it is easy to get false positives. Just because coliforms are present in the water doesn’t mean that there is sewage. Coliform bacterias are not unique to humans, so their presence could easily be caused by birds.”

Gaherty says there are a battery of other tests that can give more precise information about what’s in the water. Testing for coprostanol, for example, which is a biomarker for human fecal matter. Another test that could indicate the leak of sewage from septic systems would look for optical brighteners, which are used in laundry detergents.

“The other way to approach this is to simply start asking people,” says Gaherty. “You check out the boats where people are living, and if they don’t have holding tanks you can know for sure what the people on board are doing with their waste. Then you start taking a hard look at the septic systems on shore. The times I’ve been to Bowen, I’ve noticed that because of the hills, the best place to park is often right on the septic bed. The weight of a car can crush the pipes and cause leakage, so that is something to look into.”

Bruce Russell says that he supports the municipality’s decision to conduct an environmental assessment to get this issue sorted out.

“The Friends of Mannion Bay’s mandate only goes so far but we hope to be a catalyst that can support stopping the contamination of the Bay,” says Russell.