Metro Vancouver’s announcement two summers ago of a 97 hectare land purchase at Cape Roger Curtis rocketed the topic to the top of Bowen Island discourse. The simultaneous news that the organization planned to develop a campsite alongside a new regional park ensured it stayed there as residents shared their thoughts on the plan through a flood of letters and social media posts, appearances before council, and a sizeable petition which boasted much of the island’s adult population.

Metro’s initial enthusiasm for their project hit roadblocks from the start. Local opposition quickly proved significant, and while there were many reasons for this much of it centred on the impact that thousands of added park visitors would have on the island, both at the Cape and throughout the rest of Bowen. The camping aspect proved particularly contentious given the island’s current stance of not allowing the practice, hence the need for Metro to apply for a rezoning application in the first place.

The municipal election later that fall – a vote where the proposed park played a formative role – also left Metro to deal with a new mayor and mostly new council, one with significantly different views toward the project than the previous group which had been encouraging of the plan. While Metro scored a victory when their application passed a first reading the following spring, it was made clear that significant changes would need to be reached through meaningful engagement to make the park more sustainable with regards to several factors including visitor management.

Engagement came and went, but substantive changes to the project did not. Despite substantial local feedback, and council producing their own list of conditions they wished to see addressed, Metro’s vision for the land remained largely the same, notably the total number of proposed campsites which sat around 100.

“Phase 1 of engagement as stated by Metro Vancouver was intended to be a listen and learn – listen to our community, learn what’s happening, and that input was to feed forward into their overall park concept design that was unveiled in Phase 2. In the summer during the open houses when Phase 2 was unveiled, there was some dismay – shared by myself – that we didn’t see any sort of changes to the underlying proposal or the park concept,” said Mayor Andrew Leonard in September 2023 following a summer of engagement. Combined with the development that August of Islands Trust finding the park plan violated 10 of their policy statements, the park concept stalled heavily and has been largely dormant since last fall.

“My belief is that the application and the underlying concept at this point – from everything we’ve heard from the community, from our staff, and that I’ve experienced firsthand – is that there needs to be significant changes made to this that address the impacts of this project. And those haven’t been sufficiently addressed,” said Leonard in October 2023.

.png;w=960)

During the back-and-forth between the municipality and Metro, another player was hard at work with their own hopes for the land. The Bowen Island Conservancy, a registered charity known for land preservation around the island including the Wild Coast Nature Refuge – coincidentally also at the Cape and a direct neighbour to the proposed Metro park – came forward to declare an interest in working with Metro to help protect and sustainably develop their new purchase. But a Conservancy proposal in spring 2023 to partner with Metro did not initially progress.

“We went to them and said we’re interested in partnering with you to keep conservation values firmly in place, particularly on the coastal lots… We could potentially come up with funding of a certain amount that would enable us to collaboratively work on this. And at that time they said we’re not interested,” says Conservancy president Owen Plowman.

This led to a surprising announcement later that summer – the Conservancy now had $20 million to offer Metro in exchange for one of the 24 lots, protective covenants on the remaining land, and an agreement not to have any camping at the Cape. By fall the Conservancy had grown their purse by eight more figures, and were now offering Metro $30 million for the entire 97 hectares.

“People contributed sums ranging from $100 to much more than that,” explains Plowman on how the Conservancy raised the staggering amount so quickly. “What we discovered was that by explaining what we wanted to do and why, people were willing to give us money. It’s gratifying that we were able to get to that sum.”

Plowman says it was around this time that discussions about a sale became more serious. Having reached a breakthrough with Metro on their willingness to sell, conversation turned to what would be included in the deal.

“I think what both parties were interested in was alignment of conservation values,” says Plowman, noting especially the pair’s emphasis on protecting the coastal lots. “They (Metro) wanted to see minimal damage and not much human impact. And that’s definitely what we want because those coastal lots are quite fragile and have the bluffs and dry lichens, some of which are very rare.”

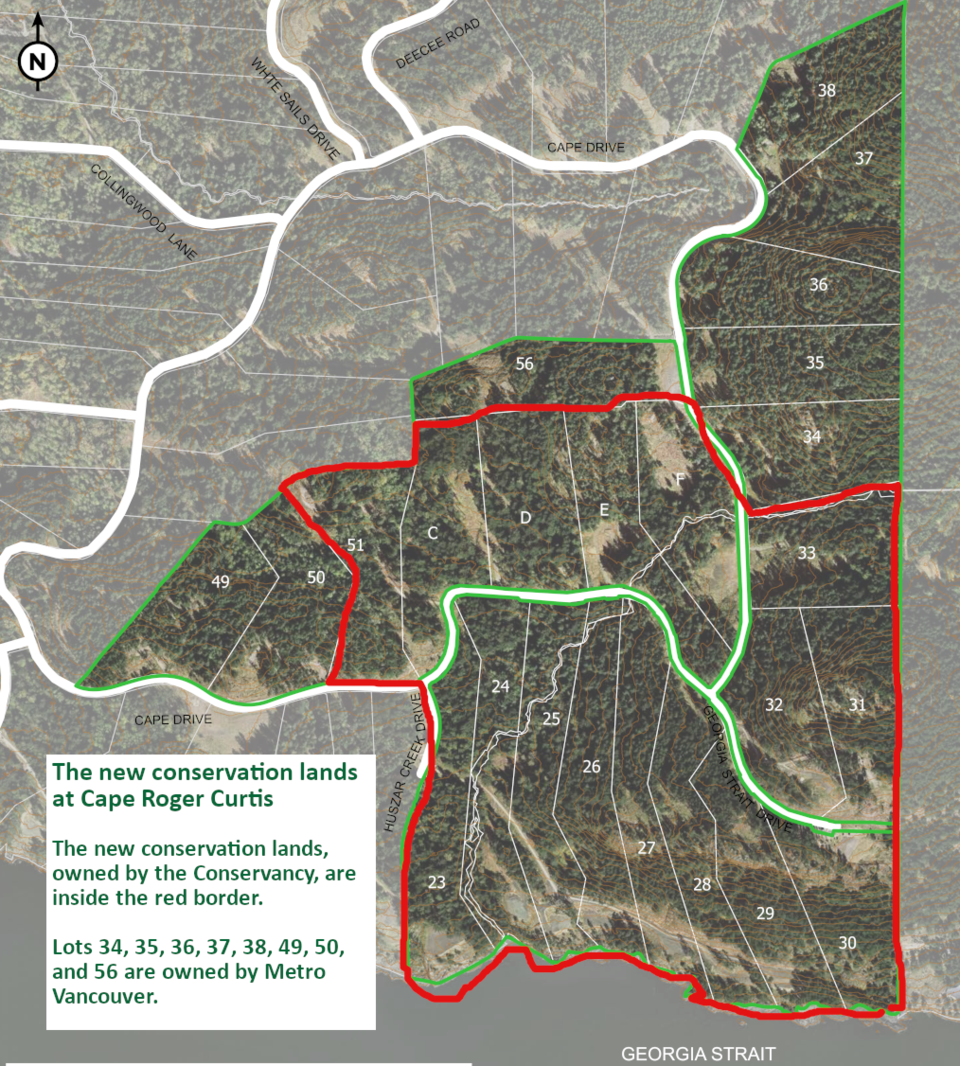

With the eight coastal lots secured, the Conservancy turned to their science advisors to see which other properties would be desirable. Together the group decided on eight more lots, which Plowman excitedly points out includes the Huszar Creek Riparian Zone as it runs down from the Fairy Fen Nature Reserve to the east.

In the end, the Conservancy obtained 16 lots totalling 65 hectares in the sale, which closed for $30.5 million. Friday’s news of the sale also brought with it a conclusion to the most contentious aspect of the more than two-year park saga – Metro would be withdrawing their rezoning application which would have allowed camping at the Cape.

“I think the objectives of conservation and allowing camping are somewhat in opposition to each other,” explains Plowman. “I think there’s ways to make it work, but the way that they proposed to make it work – which was not particularly consultative or collaborative with the residents of the island, and did not really take into account the transportation impact of having to take a ferry – really did not work in their favour.”

With regards to what the Conservancy will do with the land, Plowman says developing a management plan (which will not include camping) will centre on the group’s mandate to preserve and protect. But they also want to make sure people are able to enjoy and appreciate the space as they always have.

“We’re not an organization which is interested in fencing properties off. We believe in public education and signage, which we hope will discourage people from going into particularly sensitive areas. We would like to have people use the lands as they have throughout the years,” says Plowman, noting the roadblock preventing vehicle access to the coastal lots will soon be removed.

“This is not just for the Conservancy, this is an outcome that we hope will be of benefit to the residents of the island and visitors to the island… It’s worked out very well and it’s a win for all parties,” says Plowman. “I think we will all be very pleased.”

With plenty on their plates for now, and having just achieved a massive result in their lengthy quest, the Conservancy plans to take a step back from major developments until the new year. 2025 will likely bring with it more detailed direction for the new space, and potentially even pursuit of one or some of Metro’s remaining lots. Plowman says this will depend on funds available, though doesn’t believe there is a rush as Metro hasn’t announced any plans to develop their eight sites.

It will also be a chance for Conservancy members to take a break and reflect on the central role they’ve played in one of the formative chapters of Bowen history.

“It’s been a journey with everything you get on a journey. Breakdowns, interruptions, unplanned things happening, surprises – some pleasant, some not so pleasant – it’s been an interesting ride. At times it’s extremely stressful. But we’ve got a great outcome,” says Plowman.