I was born in the decade following the war—a baby boomer. No one talked about the war in our house, yet it affected my family daily.

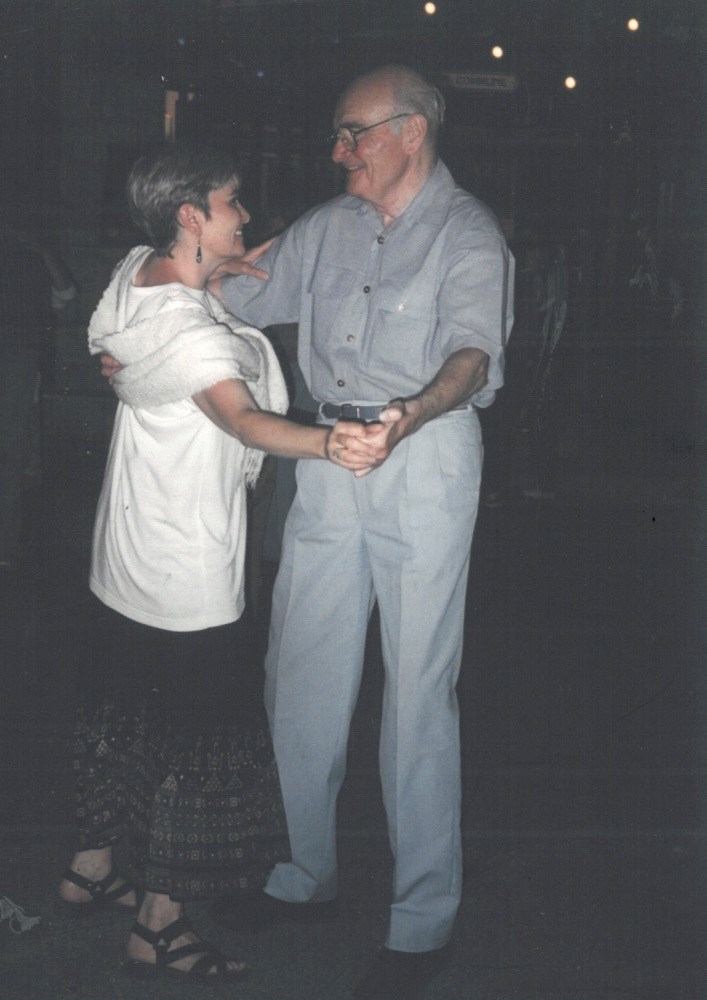

My father, Stanley Cameron, joined the army when he was 22. He hadn’t wanted to because he felt himself to be a pacifist, a difficult stance when his future father in-law was a lieutenant-colonel. But as news began to reach beyond Europe about the atrocities and suffering, he felt he had to put his pacifism aside. In quick succession he enlisted, married and was shipped overseas in 1942. He returned home to Edmonton in 1944, having been shot with a bullet that entered his throat and came out his back.

By the time he returned, my older brother was two. My mother told the story of taking him to the hospital so father and son could meet for the first time. After the visit, my brother asked when they were going to see his dad. Families around the world faced similar difficulties reuniting after the war.

My father never spoke of the war and he never complained, but it had a profound effect on his life. He had been the captain of the University of Alberta basketball team and now he had a crippled hand and nerve damage in one leg. His hand and arm gave him pain for the rest of his life. As well, he couldn’t tolerate loud noises or even not-so-loud noises. We were four children, raised in a house of unusual quietness. If our telephone rang, we never hollered up the stairs after whomever the call was for; we always walked up to tap on their door.

I was in my 40s when I learned that the unnerving calm with which my father expressed himself at times when others would be shouting was not due to magnificent self-control but to the fact that his vocal cords were damaged. Raising his voice was an impossibility. In an odd way, it was a relief to know that in my wild teens I really had managed to infuriate him after all.

I don’t think I truly understood the impact the war had had on my father until he was visiting me, my husband and our children one Remembrance Day. We were watching a ceremony on television when he burst into tears, jumped up and left the room. He apologized afterward. He explained he had suddenly been struck by the memory of a friend who had been shot and killed the day after the cease fire because the message hadn’t reached where he was fighting. Remembering the senseless loss overwhelmed him.

If my father were alive today, I know my writing about him would make him uncomfortable. But nonetheless, I think it’s important we remember the lasting trauma war inflicts on those who are sent to the battlefields, even if they themselves hold their suffering close and endeavour not to share it.

Remembering can help us take action against racism and other forms of exclusion and privilege. It can help us construct a collective moral compass founded on compassion and tolerance. Remembering the consequences of war can guide us toward creating a world in which no one feels compelled to abandon their pacifism.

-Elaine Cameron (daughter)