The most active underwater volcano in the North Pacific Ocean is primed to erupt in an event that could help scientists fine tune their understanding of what triggers volcanic activity.

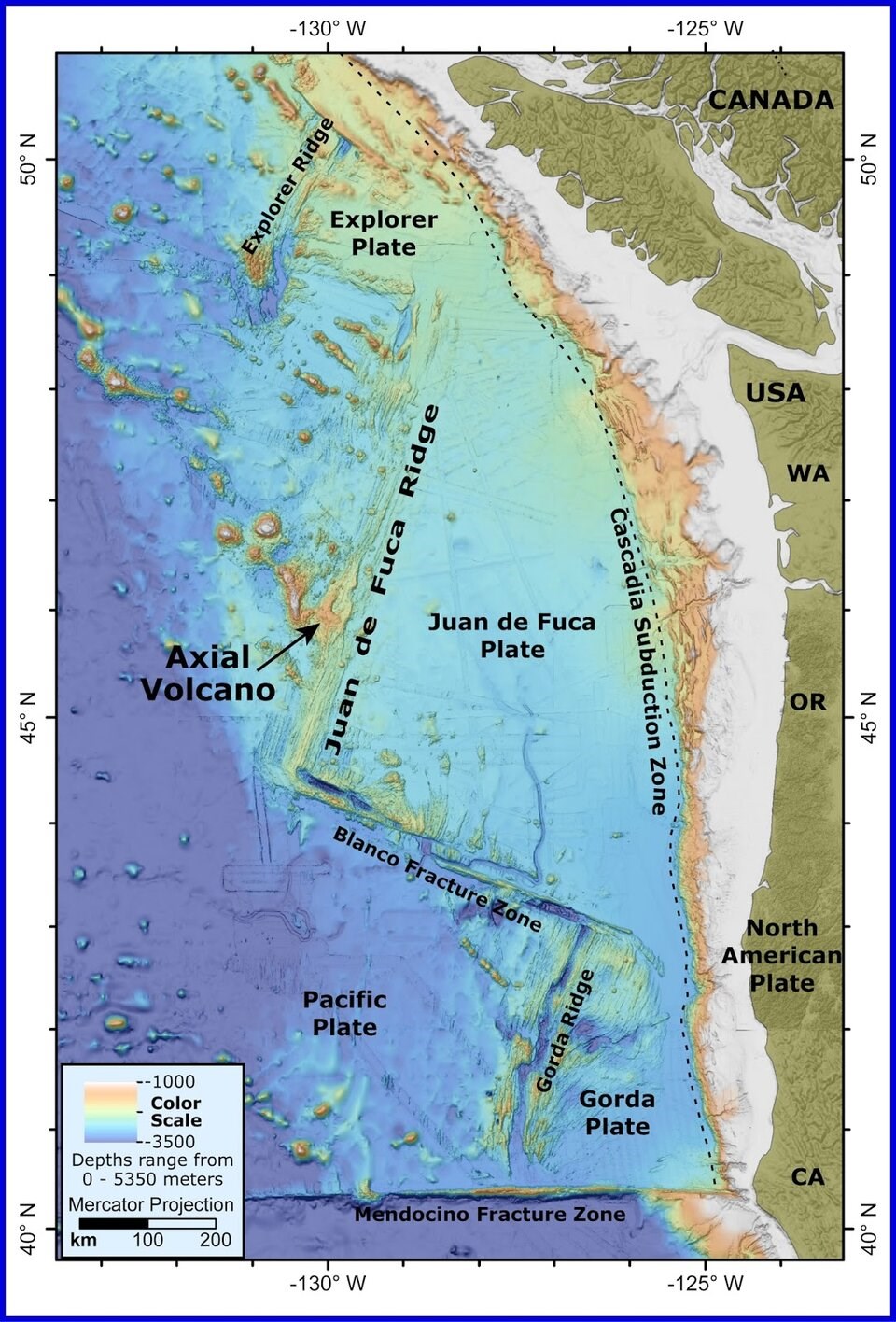

About 470 kilometres off Vancouver Island, the Axial Seamount rises from the underwater mountain range known as the Juan de Fuca Ridge.

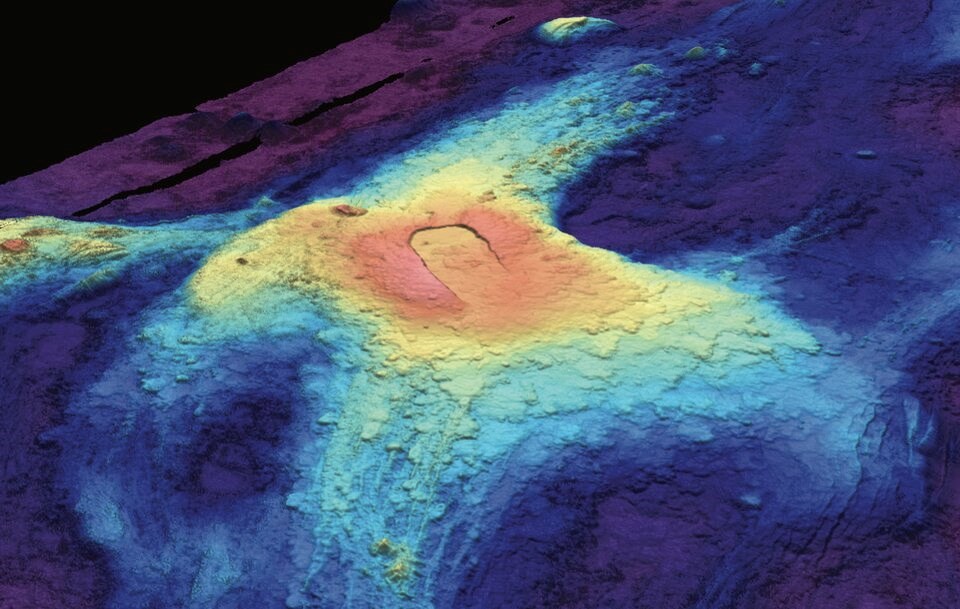

The volcano is shaped like a warrior's shield, about 25 kilometres wide and 1.1 kilometres tall. Its summit lies 1,400 metres below the surface of the ocean and is capped by a massive caldera. Oregon State University researcher Bill Chadwick has been studying the volcano for years.

“It’s pretty remarkable,” said Chadwick in an interview Thursday. “It’s the most active submarine volcano in the northwest Pacific, including the ones on land.”

Axial Seamount last erupted in 2015, and after a period of dormancy, the volcano began to inflate with magma again in early 2024. Chadwick led an expedition to the site last June to deploy equipment that would capture any future eruption. Today, real-time data is beamed back to the coast through an undersea cable.

In December, Chadwick presented data to the American Geophysical Union that showed the volcano had quickly inflated with magma amid an uptick in seismic activity — including over 100 earthquakes a day — since January 2024.

Unlike mountains on land, the underwater ridge marks the border where the Juan de Fuca and the Pacific oceanic plates separate. As the tectonic plates spread, they allow molten rock to bubble to the ocean floor, adding to the underwater ridge.

Kate Moran, CEO of Ocean Networks Canada (ONC), said her team runs a similar ocean observatory that would pick up any seismic activity at Axial from the Canadian side.

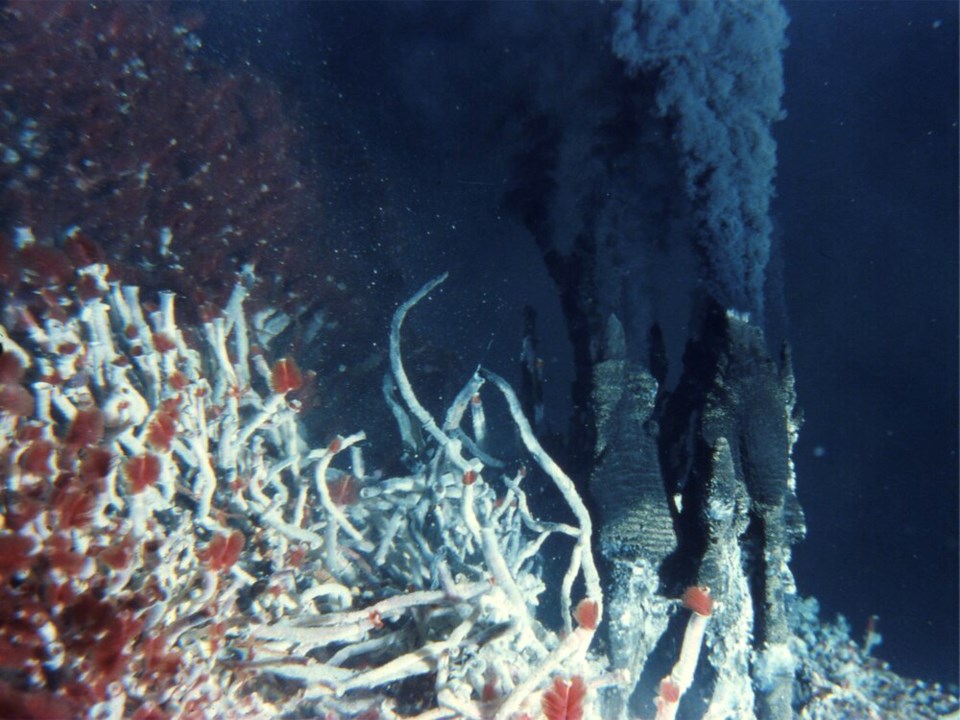

Those sensors extend to a northern segment of Juan de Fuca Ridge known as Endeavour. Here the spreading sea floor opens up active hydrothermal vents that form the backbone of a thriving deep-sea collection of life.

In March 2024, real-time monitoring of the Canadian site measured up to 200 earthquakes an hour. Since then, ONC scientists have begun developing a fast-reaction plan should seismic activity spike again.

“That means that we’ll have real-time sensors if there’s magma spewing up and spilling onto the sea floor,” said Moran. “We want to get out there and sample.”

Moran said having two monitoring networks on the same underwater ridge is not common. She said it offers an opportunity to understand how the surface of the Earth is created and lost deep under the ocean.

What’s different about the Axial Seamount is it also sits on top of a magma hotspot, similar though less potent to magma hot spots that created the islands of Hawaii and Iceland.

In between eruptions, the accumulation of magma under Axial pushes up the sea floor up to 3.5 metres. Chadwick said they’re trying to use that cycle to forecast the next eruption.

“It seems like we’re getting close. My current forecast window is it should erupt by the end of 2025,” Chadwick said. “It’s kind of an experiment to see if it works.”

When it does erupt, slow moving lava will likely emerge out of the caldera first, spreading along a fissure that follows the undersea ridge. As more and more lava oozes out, large flows more than 100 metres thick will likely flatten out around the volcano, opening up new hydrothermal vents and wiping out life surrounding the old ones.

“It’s a very benign volcano unless you’re a tube worm,” said Chadwick. “There’s death and rebirth happening at the same time.”

The researcher said Axial itself poses almost no risk to human population centres on the U.S. or Canadian coasts — the seamount is not expected to trigger displacements that could lead to a tsunami and it is far from the Cascadia subduction zone where it could set off a larger earthquake.

Many of the volcanoes that pose the biggest dangers to humans are on land and have longer dormant periods.

Axial has erupted three times since 1998. Eruptions of the 28 land-based volcanoes across B.C. and the Yukon, by comparison, occur on average once every 200 years, according to Melanie Kelman, a volcanologist at Natural Resources Canada in Vancouver.

Some, like Mount Garibaldi, haven’t erupted for 10,000 years, said Gio Roberti, a scientist working on natural hazards and climate risk at the Vancouver-based company AISIX.

When Garibaldi does erupt, Roberti said it would be more similar to Mount St. Helens: a big explosion. He said more scientific studies are being launched across B.C. to better understand threats from volcanic activity.

“As of now, we don’t know. We don’t know the probability of an eruption,” Roberti said.

That’s why Axial’s regular eruption patterns have captured the attention of scientists, and begged the question: could the undersea volcano help forecast volcanic eruptions around the world? Could it save lives?

As Chadwick put it: “We learn the most about how volcanoes work by catching them in the act.”