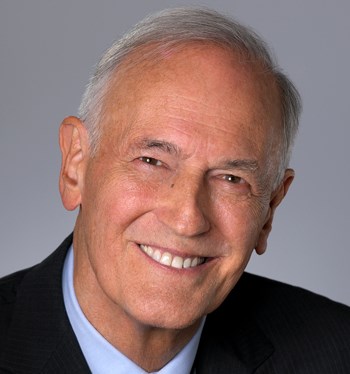

The passing last week on his 80th birthday of media executive Phil Lind was a profound loss to British Columbia, even though he lived and worked and was born in Toronto. The Rogers Communications Inc. vice-chair was a loyal, determined and prolific contributor in this province – his home away from home – in not only the expected realm of business but in education, arts, environment, First Nations, discourse and sport.

Lind joined the company in 1969 when it had two radio stations and about 10,000 subscribers dabbling with a new technology called cable television. For decades he bore the moniker as the right-hand man to one of Canada’s most visionary business leaders of the last half-century, company founder Ted Rogers.

But he was arguably as much renaissance as right-hand, a spirited intellectual as well as a no-nonsense executive who opened the eyes of the company and its founder repeatedly. As the company’s most constant principal for more than a half-century, today its $15.4 billion in annual income includes not only cable and radio but telephony, Internet, mass media, major-league sports interests and 22,000 employees.

Jimmy Pattison, at 94 the province’s most accomplished businessperson, told me Phil provided Ted with “common sense, which is not that common, by the way,” in regular instalments. “He was a really good balance. He was there with him all the time. He was the person who would say, ‘This is a very good idea, but . . .”

“Definitely,” said schoolmate Jake Kerr, the lumber baron and former Vancouver Canadians baseball team co-owner. “He was the presence of common sense.”

In interview upon interview, what emerges is how Lind was a creative force of his own, through the growth of cable television into broadcasting, through the pioneering road into cellular technology, through the broadened appreciation of British Columbian artists like Rodney Graham and Jeff Wall, through the encouragement of wider involvement of Indigenous business, through the recognition of environmental imperatives as the founder of the Sierra Club of Ontario, through the purchase of the Toronto Blue Jays and shares of other Toronto major-league franchises, and most recently through the largest and one of the most rugged corporate mergers in Canadian history.

Of that $26 billion deal to buy Shaw Communications, Rogers CEO Tony Staffieri called him a “key architect” and “a force to be reckoned with” in negotiating with the Shaw family, in articulating new investments in B.C. and Alberta, and in cultivating deep relationships. Lind devoted particular attention to Indigenous relations in the expansion of Rogers services in the province; the Coastal First Nations alliance in the North and Central Coasts and Haida Gwaii will recognize him posthumously in October.

There was always, it seemed, one eye on B.C. as he operated from Ontario. “He was a very proud UBC grad and a very proud British Columbian,” said former University of British Columbia president Martha Piper. “Phil was intrigued intellectually, had a passion for learning and for dialogue.”

He told her: “I’d like to bring great minds to UBC.’” It started with luring Harvard’s Paul Quirk to be the endowed Phil Lind Chair in U.S. Politics and Representation, then in 2015 the ambitious Lind Initiative to bring notable Americans each year to UBC to speak and teach.

“It turned out he was an intellectual peer,” Piper said. Unlike many benefactors, “he didn’t want a building – he wanted programs.”

In the case of his arts support, though, Lind thought bricks and mortar mattered to advance British Columbia. “He said it was not good enough to be a collector and decorate your house – for that to happen, you need buildings,” recalls Polygon Homes founder, art collector and philanthropist Michael Audain, whose own museum is in Whistler. Thus Lind’s persistent, often frustrating support as a board member to build a new Vancouver Art Gallery.

The many headline achievements bear noting several softer, lighter touches: the adoration of Animal House as a film extension of his UBC frat house, the dark humour he’d utter about his beloved and hapless Cleveland Browns, the practical jokester and the fly fisherman who until last year Kerr said “never, ever let up.”

It would have been understandable had he done so, due to another defining event that made his life so remarkable. For a quarter-century, Lind contended with the effects of an intense stroke that seized him on Canada Day in 1998 and rendered extensive right-side paralysis. Within a year, he was back in the office. He rebuilt his capacity to speak and walk and had taught himself how to write with his left hand – more legibly, he reported. He demanded he be treated no differently.

“How he managed with a stroke was inspirational,” said Piper, educated as a physical therapist.

“I was just astonished at his fortitude,” Audain said.

“Never, ever asking for sympathy,” recalls Bob Rennie, a fellow art collector and the province’s most prominent real estate marketer. “He just carried himself with such strength.”

And he carried along. “Being in the middle of the action with Ted Rogers is hard to give up,” Pattison noted. “But it was so impressive.”

In Rennie, he found someone he could debate over the future of the gallery.

“I felt so comfortable that we had a dialogue we needed to have,” Rennie said. “He allowed constructive conversations around it . . . There was a fairness to him. He didn’t make you feel you had to side with him.”

Which is not to suggest he wasn’t anything but persuasive. Take, for example, how his love of sport extended from his love of business, and how he brought Ted Rogers in 2000 to buy the Toronto Blue Jays – “no small feat,” Kerr said, “because Ted knew nothing about baseball.” The acquisition was part of Lind’s vision for Sportsnet as a national sports network; it would later become the Jays’ television home and, in time, the dominant National Hockey League broadcaster.

Lind and Kerr would collaborate in persuading the Blue Jays to make the Canadians one of its minor-league teams in what Kerr called “the understanding of the need for a national franchise.” But what always amazed Kerr was how Lind “could change hats so quickly, from being a director, to talking about the C’s, to art, to politics.”

He worked in the backrooms as what was then known as a Progressive Conservative. Former prime minister Brian Mulroney, on the day of Lind’s passing, said Canada had lost a “great leader” who left an “indelible mark on our country. His success in business was only matched by his passion for the arts and a deep obligation to his country through his many philanthropic endeavours.” His thirst for discourse led him to launch CPAC, the national public-affairs channel and the home of House of Commons broadcasting. He was awarded the Order of Canada in 2002 and, among his many honours, was a fellow of the Royal Canadian Geographic Society.

He leaves his daughter Sarah, son Jed, daughter-in-law Jessica and granddaughter James and grandson Jack. He also leaves his brothers Ronald and Geoffrey and sister Jenifer, as well as long-time companion Ellen Roland. Lind was predeceased by former wife, Anne (Rankin) Lind.

“I would call him a Canadian treasure,” Piper said.

“When I grow up, I want to be Phil,” Rennie said.

Kirk LaPointe is publisher and executive editor of Business in Vancouver and vice-president, editorial, of Glacier Media.