A section of a gravel and dirt roadway in Pouce Coupe does meet the definition of a public highway under section 42 of the Transportation Act, according to a B.C. Supreme Court ruling.

The roadway became a subject of contention in a civil lawsuit between the province and South Peace residents Curtis and Deanne Querin, who own a quarter section at the eastern outskirts of Pouce Coupe, with the Querins purchasing their property in 1991.

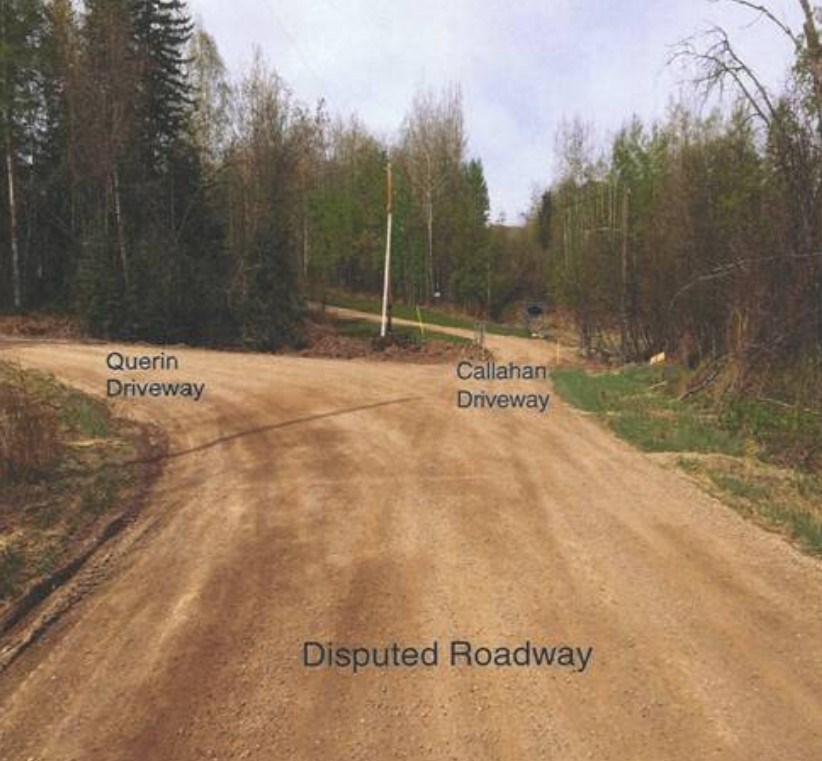

In the suit, the Querins claimed the roadway was part of their driveway, despite allowing access by the public, mainly their neighbours Dale and Barbara Callahan, who purchased a property next door in 1995.

Justice F. Matthew Kirchner explained that maintenance on the roadway dates back to the 1980s, with testimony provided by former maintenance contractors for the Ministry of Transportation detailing work on the roadway.

Further testimony also noted that the roadway had been accessed by the public in the 1960s and 1970s. A roadway is a considered a public highway if it is a “travelled road” and the province has expended public money on maintenance.

Kirchner noted the Callahans have largely been the main public travellers in the past 20 years, outside of a few other members of the public, but enough to satisfy the province’s claims.

The dispute first arose in 2015, but came to a head in 2017, after the Querins learned the Callahans were planning to subdivide their property to create a separate lot and wanted to use the roadway for access.

Upset with the idea of increased public traffic, Curtis Querin attempted to assert ownership over the roadway by posting “Keep Out” and “Private Drive” signs on the roadway, but did not initially stop the Callahans from using it.

In 2017, Curtis Querin escalated the matter by placing concrete blocks across his own driveway and the Callahans’ driveway, which blocked the Callahans from entering their own property.

This was a major concern for the Callahans, as Barbara Callahan has an aortic root aneurism which requires regular medical attention, and she was prevented from attending a medical specialist appointment on the day the blocks were installed.

Curtis Querin also installed a locked gate near the east end of the roadway, and claimed he did it because road contractors were turning their trucks and machinery around in a lay-down area on a northeast part of his property.

The Callahans then asked the RCMP and the Ministry to clear the road, but RCMP said the matter was a civil dispute and refused to get involved.

On January 26, 2018, Barbara Callahan wrote to David Eby, then the Attorney General, asking for assistance. Not long after, ministry representatives and contractors removed the blocks and the gate from the roadway.

An injunction was put in place by the province to keep the road clear, until the matter was settled in court.

The province had sought damages against the Querins for the cost of removing the gate and blocks in the amount of $4,727.25, but the ask was dismissed by Kirchner.